2026 Author: Leah Sherlock | sherlock@quilt-patterns.com. Last modified: 2025-06-01 06:56:42

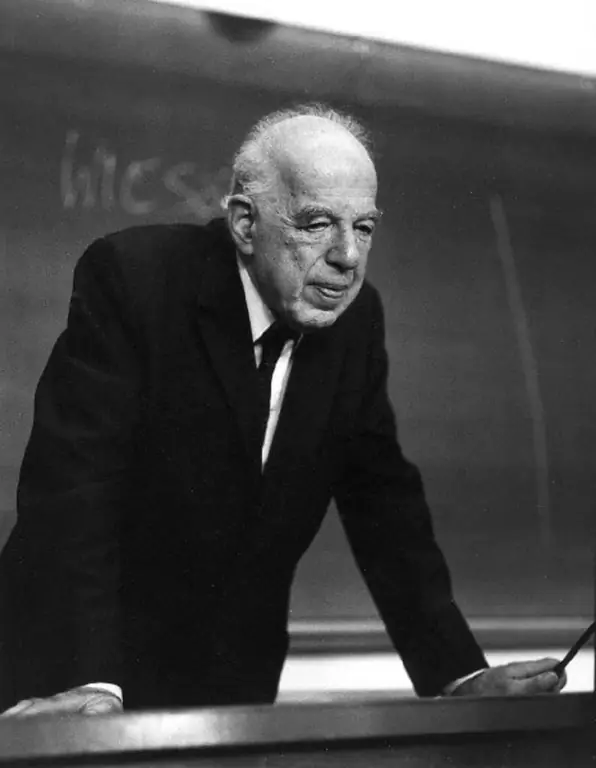

The Austrian-born British writer and educator Ernst Hans Josef Gombrich (1909-2001) wrote a seminal textbook in the field. Reprinted over 15 times and translated into 33 languages, including Chinese, the book has introduced students from all over the world to European art history.

His History of Art was successful in part because it was accessible and philosophical. It also contained many of his new, original ideas about the nature of art, which the author subsequently developed in his many subsequent works. A man whose curiosity and interests ranged from ancient Greek sculpture to teddy bears, Gombrich was an influential educator in both Britain and the United States and generally regarded as one of the most insightful thinkers of his day.

Childhood

The biography of Ernst Gombrich was very rich. He was born in Vienna (Austria) on March 30, 1909. His family was Jewishorigin, although she adopted the Protestant faith. His father, Karl, was a lawyer and official in the Austrian Bar Association. His interest in art may have been inherited from his mother, Leoni, who studied music with the composer Anton Bruckner and turned the pages of sheet music for the even greater Viennese composer Johann Brahms. Ernst Gombrich himself became a good cellist. Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud was a family friend.

The First World War affected the financial situation of the family. Allied border controls after the war led to widespread famine in Vienna; Ernst Gombrich and his sister were sent under the auspices of the British charity Save the Children to live with a Swedish coffin carpenter for nine months.

Study

After returning to Vienna, he attended a secondary school called Theresianum, suffering from the impatience of his classmates, because studying was too easy for him, while he learned a lot on his own. He was interested in art from the very beginning and wrote a long essay on art history while still in high school, but his interest spanned many different subjects.

At the University of Vienna he studied with one of the most influential founders of modern art history, Julius von Schlosser. He wrote a dissertation on the sixteenth-century Italian painter Giulio Romano, successor to Michelangelo, and had a gift for explaining art to young people. Ernst Gombrich believed that the features of works of art were the result of the efforts of artists associated with solving problems specific to their own.situations, and not the vague spirit of the times or the peculiarities of historical development. This approach was to become central to Gombrich's mature writings on art. He obviously enjoyed writing for children; his first book, published in 1936, was Weltgeschichte für Kinder ("A World History for Children"). It has been translated into several languages.

Flight from Austrian fascism

In 1936 he married the pianist Ilse Heller, they had a son, Richard, who became a professor of Sanskrit. Ernst Gombrich could already see at that time that his parents' conversion to Protestantism meant nothing to the new fascist government of Austria. He left the country, taking a job as a research assistant at the Warburg Institute in London, a private art library that moved its collections from Germany to England as cultural life in Germany deteriorated significantly under the Nazi regime. In 1938, he was able to help his parents escape from Austria. That same year, he began teaching art history classes at the Courtauld Institute in London, and began writing a book on caricature with fellow art historian Ernst Kris. The book was never published, but it was at this time that he began to use the name E. H. Gombrich, as he was annoyed by the double "Ernst" that was supposed to appear on the title page.

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Gombrich began serving his new country with the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), translating German broadcasts for intelligencepurposes. He remained in this post until the end of the war in 1945, using the job as a way to learn to write well in English, and when Adolf Hitler committed suicide, Gombrich personally delivered the news to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

A look at art

After the war, he returned to the Warburg Institute and resumed work on the book that became The History of Art. Ernst Gombrich began writing it in 1937 in response to a commission from the publisher Weltgeschichte für Kinder and was initially aimed at younger readers. However, the author's clear, accessible style proved ideal for students of all ages. The History of Art was published in 1950 by Pheidon. He did not write it with his own hand, but dictated it to the secretary. “In fact, art does not exist,” the writer began the text. - "There are only artists."

The author meant that art was the result of the efforts of artists to solve specific problems at a certain time. He was not interested in seeing art as an eternal pursuit of beauty. “If you try to formulate the principle of beauty in art, someone can show you a counterexample,” he said, quoting the Times London newspaper. And he never collected art. Nor did he see it as an expression of some vague zeitgeist. Sometimes he can connect art with philosophical ideas, but only in a very specific way. Instead, Gombrich considered situations in whichspecific works of art: who ordered them, where they should be placed, what they were supposed to achieve, and what technical difficulties the artist faced as a result of these factors.

University professor

The History of Art by Ernst Gombrich has always attracted critics. He had little sympathy for modern art, with its emphasis on formal principles and its relentless innovation, and he did not explore in depth the art of the non-Western world. This book, however, produced a new generation of students with a fresh understanding of familiar pictures, and his academic career took off quickly after its publication. Liaising with the Warburg Institute (later part of the University of London), in 1959 he became its director. But he also had experience as a professor of art history at Oxford (1950-53) and Cambridge (1961-63), as well as at Cornell University in New York State (1970-77). In addition, he has given numerous visiting lectures. From 1959 until his retirement in 1976 he was Professor of the History of the Classical Tradition at the University of London.

Key Ideas

In public lectures, such as the prestigious Mellon Lecture Series he gave in Washington, DC, in 1956, the eminent art theorist did more than just make interesting presentations. He regarded them as occasions for serious reflection and took the opportunity to formally develop some ideas about art and psychology,underlying the history of art. Many of Gombrich's books were revised versions of lectures he gave. Art and Illusion (1960), one of the best known, was based on Mellon's 1956 lectures and explored the importance of convention in the perception of works of art. Gombrich argued that artists can never simply draw or draw what they see, but depend on representations based on expectations derived from what viewers have already seen.

In his lectures and writings, Gombrich expanded his psychological ideas. In later years, he liked to use examples of drawings of people that were tentatively sent out in unmanned aerial vehicles around the universe in order to communicate something about people and their place in space to any alien beings. Any such alien, Gombrich pointed out, would have no frame of reference for interpreting the crude drawings of people they could find: if they didn't have human hands, they would, for example, think that a woman whose hand was depicted on one from the drawings, actually had claws. Gombrich applied the same reasoning on a more specific level to known paintings and to the assumptions that the audience made when they viewed them. He was fascinated by new forms of presentation that depended on representational assumptions, and he once wrote an essay on teddy bears, pointing out that they were a characteristically modern phenomenon.

Literary activity

Some moreGombrich's later books, such as The Gun Caricature (1963) and Shadows: A Description of Cast Shadows in Western Art (1996), de alt with specific topics within his more general field of ideas about psychology and representation. Other books were collections of essays and speeches on various topics; some of the more widely read included "Meditation on a Horse - a Hobby" and "Other Essays on the Theory of Art" (1963), "The Image and the Eye: Further Studies in the Psychology of the Image" (1981) and "Themes of Our Times: Problems in Learning" and art" (1991). Between 1966 and 1988 he also wrote the four-volume series "Studies in Renaissance Art" and maintained a lifelong interest in the art of the ancient world.

Modern times

Despite the reliance of his ideas on modern psychological science, Gombrich cannot be called a supporter of modern art. One of his most widely read articles appeared in the Atlantic in 1958; he called it Vogue of Abstract Art ("Fashion for abstract art"), but the editors gave it the more provocative title "The Tyranny of Abstract Art." He disliked what he saw as a preoccupation with novelty in twentieth-century art, and devoted the book The Ideas of Progress and Their Influence on Art to the question of art and its relation to the ideologies generated by technological change. However, Gombrich has never been categorized as a strict conservative and has spoken out in defense of some contemporary artists, including the semi-abstract British sculptor Henry Moore.

Banyway, he lived long enough to see the fine arts come to the fore again. Gombrich remained active in the last years of his life, continuing to write and lecture despite declining he alth. He died in London on November 3, 2001, with enough work on his desk to publish a posthumous volume, Preference for the Primitive: Episodes in the History of Western Taste and Art. By that time, about two million copies of The History of Art had been sold. Gombrich's intellectual legacy was enormous, extending to art history classes at numerous community colleges, where a teacher could point out some distortion of reality in a famous painting and ask the students in attendance why the artist could have done it this way.

Ernst Gombrich Awards and Prizes

Outstanding art critic was Commander of the Order of the British Empire (1966); holder of the British Order of Merit (1988) and the Vienna Gold Medal (1994). In addition, he is the recipient of the Erasmus Prize (1975), the Ludwig Wittgenstein Prize (1988) and the Goethe Prize (1994).

Recommended:

Khadia Davletshina: date and place of birth, short biography, creativity, awards and prizes, personal life and interesting facts from life

Khadia Davletshina is one of the most famous Bashkir writers and the first recognized writer of the Soviet East. Despite a short and difficult life, Khadia managed to leave behind a worthy literary heritage, unique for an oriental woman of that time. This article provides a brief biography of Khadiya Davletshina. What was the life and career of this writer like?

Venice Festival: best films, awards and awards. Venice International Film Festival

The Venice Film Festival is one of the oldest film festivals in the world, founded by Benito Mussolini, a well-known odious personality. But over the long years of its existence, from 1932 to the present day, the film festival has opened to the world not only American, French and German film directors, screenwriters, actors, but also Soviet, Japanese, Iranian cinema

Yakovlev Vasily: biography of the artist, date of birth and death, paintings, awards and prizes

"I learned from the old masters." What does this phrase, once uttered by one of the most famous Soviet portrait painters, Vasily Yakovlev, mean? In search of an answer to this question, it turns out that this artist, unlike many of his comrades, did not draw inspiration at all from the paintings of recognized masters - Serov, Vrubel, Levitan and other equally famous personalities. At the heart of his art is something much more personal, intimate. What? Find out in the next article

Film "Island": reviews, plot, director, actors, prizes and awards

The film "The Island" (2006) has become a kind of hallmark of Orthodox cinema. This tape appealed to both believers and non-believers. After all, judging by the numerous reviews, the film "The Island" by the actions and behavior of its main character, the elder Anatoly, gave each of the viewers invaluable life lessons

Ilichevsky Alexander Viktorovich, Russian writer and poet: biography, literary works, awards

Alexander Viktorovich Ilichevsky - poet, prose writer, master of words. A person whose life and personality is surrounded by a constant halo of loneliness and renunciation. It is not known for certain what was the root cause - a hermit's existence away from the media and secularism gave rise to his unusual literary works, or prose and Russian poetry, far from the mind of the inhabitants, influenced the author's detached lifestyle. Russian poet and writer Alexander Viktorovich Ilichevsky is a laureate of many awards